A Geocache, A Stubborn Ass, A Packmule, and A Billy Goat

A primer before I start. For those who don’t know what geocaching is, it’s like adult hide and seek, with GPS coordinates leading (typically) to hidden items all across the world, where the adventure is in finding and signing the log, often hidden in public places, or taking you out to amazing locales across the world. This cache falls in the latter category.

About six months ago, my father in law, an avid geocacher, heard about a cache that can be “claimed” by visiting a cemetery near the headquarters of Burning Man in Nevada, followed by a hike to the most remote ghost town in California, down in Death Valley. The cache, though posted in 2002, had only been found four times, yet was on the bucket list for many cachers. When word of a potential archival of the cache came downwind, the drive to get this cache by Robert went from desirable to urgent. Within weeks, he had put together a team of himself, the geocaching guru, his son, the young, fit, and energetic one, and myself, who he just called “the brains.”

The location of the ghost town, Beveridge CA, lies between the Inyo Wilderness area and Death Valley. It’s situated in a valley about 5,000 feet in elevation, where a spring supplies water down the gulch. Getting into the town means about 6,900 feet of vertical ascent, followed by 1,300 feet of descent into Beveridge Valley. Fortunately for us, several people have blogged about their trips into the town, but with multiple options in, we chose the path outlined by Matt Clapp in his blog, as it seemed the most straightforward and achievable route in.

The Preparation

Our virtual guide took the trip in two days, ten hours of hiking in, and eight hours of hiking out, with regrets at not giving himself enough time to explore Beveridge. Our drive time would be eight hours, so we knew a two day trip was not at all possible, so our plans were to give ourselves four days in total. One day for travel down and sleep at the base of the trail. One day for hiking in to Beveridge. One day to explore, and possibly grab some of the other area geocaches, and one day to return and drive home.

With this plan in place, a key part was missing for all of us. None of us had ever gone backpacking before. Probably a bad idea for a trip considered for experienced backpackers only, but that meant that we all had to make a trip to REI and pick up gear. An hour into working with the sales guy, and we were outfitted with new sleeping bags, a sleeping pad (I already had two), and Osprey trampoline-back 65L frame packs. We each tried out the whole selection of appropriately-sized packs, and we all landed with the same one for size and comfort.

Subsequent trips got us the key element which every guide had pointed us to… water storage, and tons of it. We knew there would be no water until we got to Beveridge (and hopefully the spring was still running!), and eight liters was the suggested amount. MSR makes a ten liter water bag which we figured to be perfect for the hike. Add in the camelbak-like tube, and Robert’s water pump, and a Delorme emergency satellite beacon which Robert invested in, and we were set.

Last plans were for clothing and food, which I calculated to be about 10k Calories each, and we each took slightly different approaches on. Robert packed a jar of peanut butter, tortillas, beef jerky, and salami. Vincent made some oat and Nutella energy bars. I grabbed pistachios, cashews, jerky, trail mix, and nut butters. On top of all that was five boxes of Honey Stinger waffles, which were my only fuel for my Half Ironman, and I was very comfortable with. Everyone limited their clothing to one or two items of each type. Add in the final necessities like first aid, paracord, knives, etc. and our planning was complete.

Departure and Early Starts – Friday

A 6am start from Sacramento got us to the trailhead just before 6pm. We lost about an hour to a wrong turn (Hwy 4?), breakfast and lunch added a bit of time, and our trust in Google. We Four-Wheeled it along Google’s chosen route, which took us on 4WD roads when a groomed path suitable for most vehicles existed with just a single turn. However, since the goal of this blog is the hiking,

I’ll just leave it to say, if any of you choose to go into Death Valley as we did, just take Death Valley Rd to Waucoba Saline Rd, and skip any “shortcuts” you’re offered on Waukoba Rd or other such roads. 4WD is still helpful to get you the closest to the base of the mountain, but we didn’t cut out too much more than what any SUV could have done.

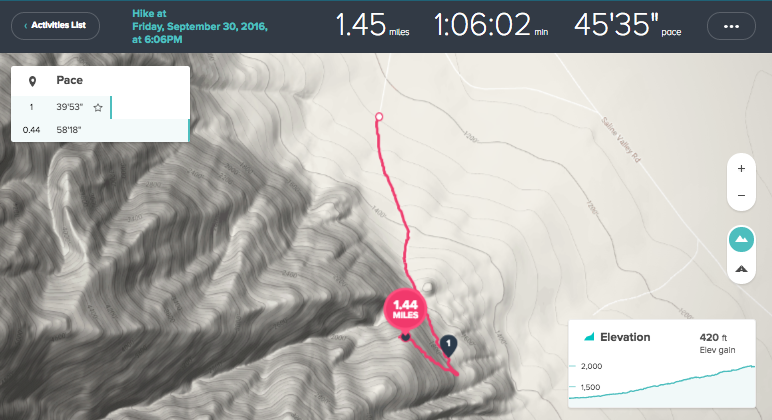

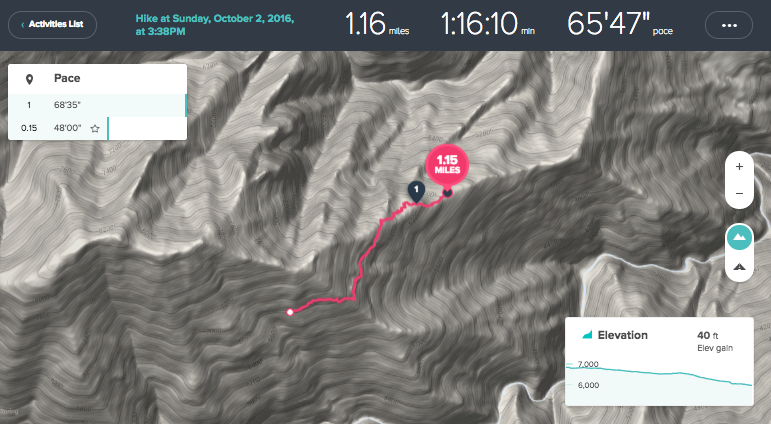

After final prep of our bags, we figured that we still had about ninety minutes of daylight left to get a head start on our journey. Had I known what finding a good campsite would be like, and what sundown really felt like on the hikes, I would never have chosen to start hiking at 6pm, but the choice this time was fortuitously good. We got our start into the trip and cut an hour out of our “day one” hike into Beveridge.

The first mile and a half of our journey was along the “road”… if it can be called that. Clearly the road existed in a usable fashion at one point, but it is now mostly a broken jumble of rocks, with a one to two foot crevice down the center, which one constantly has to jump or climb across as either “side” of the road may exist or not at any given point.

About four full washouts exist within that first mile and a half (well two, but encountered both high and low on the road), though these weren’t too difficult to navigate across. We cleared a mile and a half or so of hiking, and 420 feet of elevation gain, before dusk and the discovery of a fairly flat place to set up camp got us to call it for a night.

This was the first test: can any of us get sleep, without tents, under untested sleeping bags, in the middle of the desert night? The area was quieter than I think I’ve ever been in for an extended period of time, and while I’ve spent time in places like Yosemite Valley, and have seen the multitudes of stars visible from a more remote location, I can confidently say that I have never seen more stars than I saw that night. Death Valley is a “dark sky park”, with no civilization, no lights within the peaks, our three days were across the new moon, and the stars were just amazing.

I can proudly say, I was the first to fall asleep, and didn’t get up until dawn. It’s a very new experience to me, being in “bed” for almost twelve hours. And yet, I got somewhere between six and ten hours of sleep… I have no idea how much. Around midnight, I awoke, and just stared at the stars for countless minutes. I shifted many times during the night from one sleeping position to another. I’d awake to a body part being asleep, only to relax, and some time (five minutes? fifty?) later fall back asleep again.

We all awoke around dawn, had breakfast, and got packed up to leave once the sun arose, around 7am.

The Main Hike and Little Mistakes – Saturday Part One

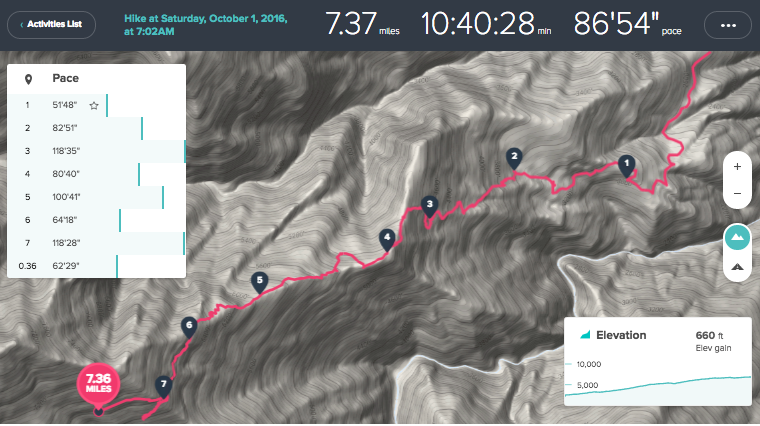

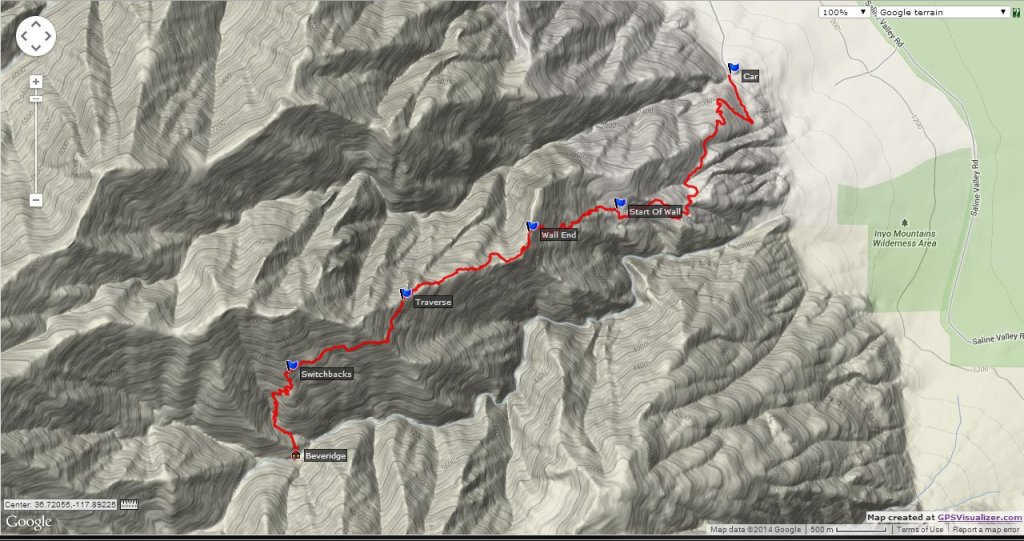

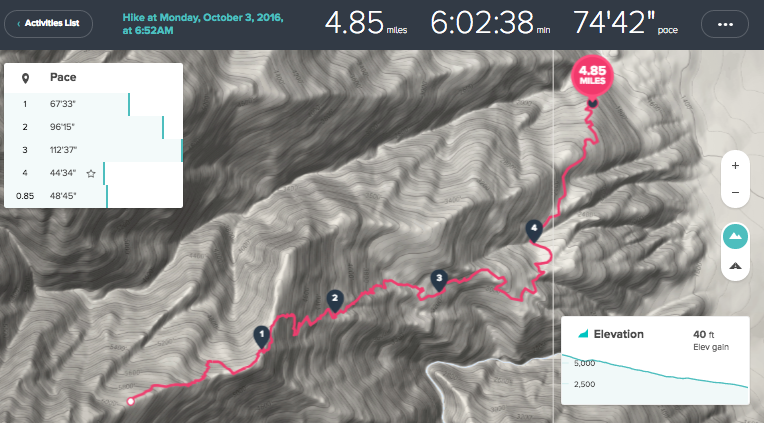

Our guide blog breaks this trek into five main parts: the road, the wall, the ridge, the traverse, and the descent. We were a mile and a half into “the road,” what our guide blog said was a 2.3 mile road with 1800 feet of climb. We’d been climbing most of the way, and so were pretty confident that we were approach the beginning of the hardest part of the journey, the great white wall. With hindsight, let me say now, that this was wildly inaccurate, and that inaccuracy eventually led to many, many bad assumptions on where we were. Eventually, I figured out a better way to gauge our progress, but at this point I was just going by the key distance elements and the “feel” of where we were.

It took us just over two hours to reach the wall, a location I was expecting to hit in just thirty minutes or so. Fortunately for us, the wall has a definite starting point, which was very helpful to getting us situated in location.

There are three posts, surrounded by rocks and chicken wire, which we were looking out for which signaled the beginning of the wall. We knew already that this would be the toughest part of the journey, and having a very clear guidepost (literally), plus the change in trail type from the road to a more traditional trail, brought us to stage two, just after 9am. We stopped for a bit, to catch our collective breaths, prepare for the next part, and set out.

The Great White Wall – Saturday Part Two

Four hours. That’s how long it took to climb the Great White Wall. Our expectations from the guide blog were this: “Start your ascent of the Great White Wall for 1600 vertical feet of switchbacks in under a mile. There is one stretch of scrambling on the ascent. Otherwise, it is a steep but walkable trail.” Under a mile, 1600 feet. Now I can’t tell you who is right: my GPS says it was over two miles, and this was my second clue into that navigational mistake that’ll come bite us later, but the blog came from a much more experienced backpacker who also was tracking his information via GPS. I hadn’t yet noticed the wide discrepancies between our guide distance and my personal distance, but eventually I will figure it out. As for the wall? Describing it as a “steep but walkable trail” is somewhat correct… at least to start. Most of it does fit that description, but definitely lacks nuance. The whole mountain range is built out of crumbling granite. That decomposed granite that gets used across all of our parks to make nice walking trails? That’s what the entirety of the mountain is. Sections of granite that look like solid hand and footholds might peel off the rock at any point, and even sections that were stable when you stopped to take a breath might shift underfoot thirty seconds later. And areas of the trail that were once walkable might now be a giant washout you have to cross.

By 1:09pm, we had finished walking the wall, guided by countless cairns placed along the trail by those who came before us, and generally made it to the top with little-to-no issues, except for some tiredness and general slow-going. At this point, done with just the first two of five main sections, and past midday, it was definitely becoming apparent that our plans may need to shift, but we were all accepting of that and prepared for the eventuality.

The Ridge, The Traverse, and the Big Oops – Saturday Part Three

At 1:35pm, Robert posted with his Delorme that we had finished “The Ridge” and begun the traverse. This mistake of mine comes from this quote:

“After reaching the top of the Great White Wall, continue climbing on the trail along the ridge.

Briefly descend to loop around the right of a peak and continue ascending on this trail until you reach the start of the traverse. Once you turn the corner you will lose sight of Death Valley and be able to spot plant growth upstream from Beveridge.”

If I had been looking at the topo maps, and not mostly the satellite maps, I would have understood the error in reading it this way. Take a look at this map:

You’ll notice that the end of the wall to the traverse is quite a long way. This is not brief… but that’s what I expected it to be. The ridge isn’t described as a three mile long ascent of thousands of feet, but by my GPS, it was. So when we looped around the peak and left what felt like the end of the ridge trail, we though we’d reached the next section. However, it just kept climbing, and climbing, and climbing. The topo version of the map makes it very clear that we were still on a ridge, but my experience with ridge trails were much more clearly along the top of the mountain lines, as we had been previously, and it didn’t feel like that then. We were still encountering many sketchy areas of washouts, loose terrain, and difficult steep-grade climbs, and it just didn’t seem to end. The actual end of the ridge was over eight hours into our Saturday hike, and took us about four hours!

Now to the big mistake. We missed some cairns. Like, five of them right next to each other, guiding us in a specific direction, and a row of rocks placed to prevent us from going the direction we did. By all distances, we should have been done with the ridge, done with the traverse, and beginning our descent, and at this point, we could now see the glorious valley that was our end destination. And we saw a cairn, possibly two. So Vincent and I began descending a VERY sketchy area of rockfall, trying to find the full trail that the two cairns were guiding us to. However, we weren’t on the path at all. The one cairn, Robert later surmised, was just an attempt by a hiker to say “I got here!” to a great outcropping that looked like the Lion King rock. We descended way farther than was safe, and finding our way back from there, after about 30-40 minutes of wrong going (look at the mile 7 marker), meant climbing up rocks and scree in order to scramble back from a very dangerous area.

Once greater prudence forced us back, we found the hugely obvious directions as we were ready to hang up our hats for the night, and pushed on a ways into what I now know was the midpoint of the traverse. It was at that point of finding our “new” correct path, that I made some key learnings. I, the “brains” of the operation, had saved into Google maps offline versions of the area. I had also saved the entirety of the blog. Using the terrain map on the blog, and the terrain map on my phone, I could coordinate the two to ensure we were on the right track, and to get a feel for how much more of any type of terrain element we had left. I could now see clearly the ridge portion, the traverse, and how far along the track we were. Even though we hadn’t had cell reception since we were on Highway 50, I could still use the technology at hand to make our navigation a more active process.

We set up camp at about 6:22pm, thankful that we were back on the right track, sure that we wouldn’t make it into Beveridge in the last 30-60 minutes of light (we hadn’t even started the descent yet!), and glad that we found a spot we could stop. At this point, the discussion turned to what the rest of the hike would look like. Collectively, at that point, we agreed that we would be departing Beveridge about noon to head back, instead of spending all day and sleeping in Beveridge as originally planned. Clearly, our pace was much slower than we anticipated, and expecting to hike out of Beveridge and drive home in one day was not realistic.

Beveridge and Footprints in the Sand – Sunday

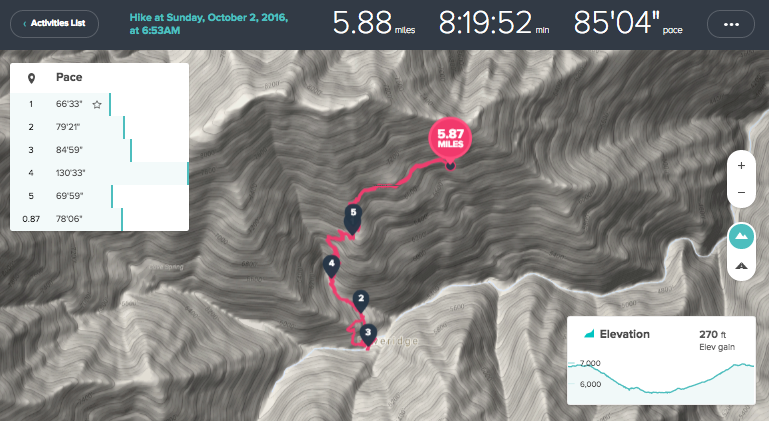

Knowing that we survived a mistake, that we were heading in the right direction, and we’d be in Beveridge that day, I would say that spirits were up the next morning. We had a clear path to travel, we were making good progress, and it felt like we had success in hand.

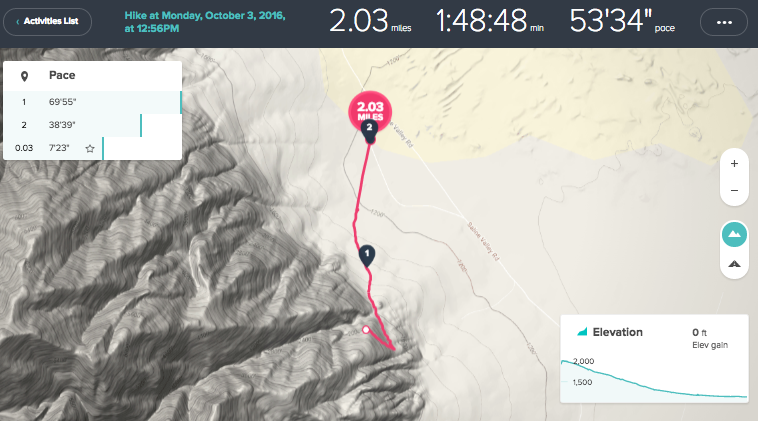

The descent into Beveridge was fairly unremarkable, except for the rattlesnake encountered by Robert. We rounded a few more “fingers” of the mountain on the last of the traverse, and headed down. We had already seen a couple of interesting remaining artifacts from the mining era along our trek in quite random places, but it was fantastic to not only begin to see the valley in earnest, but the first item we knew was directly associated with the town, the “tram”. I have no idea how it worked, but the cables stretch several thousand feet, and at one point there was a pulley still attached to the cabling. We descended the last part of the trail, after taking a few required pictures at the tram, and finally made it to our destination!

We had a few landmarks in our list to go view, but priority one was water, and priority two was getting enough pictures to satisfy the geocaching requirement. Arriving around 10am, three hours after departing that morning, we had about two hours to walk around the area, eat enough food for the trip back, and refill 30 liters of water. After snapping a few shots of the mill press, I quickly headed to the water to ensure it was still available for us to pump… otherwise we were likely calling a helicopter for a very expensive rescue. Fortunately, even after years of drought, the spring was still active and we’d be able to refill before we departed.

There only exists left in the main part of town a few key items. A large mill press, that for the life of me I can’t imagine bringing the parts in and building within such an inaccessible town, some bed frames, a couple of collapsed cabins, and two very intact toilets. One, an outhouse built overhanging a cliff so that the leavings drop down the side of the mountain, and one an open hole built over a large stone-walled opening. Above and below the town are also some other cabins, but given our two hour stopover, and the expectation that it would take that full time to refill our water, we kept our wanderings to the main part of town.

On the water, Vincent and I started trying to refill my Nalgene bottle. About fifteen minutes of pumping later, and we had gotten about 400ml filled. Not a good omen for doing 10L worth of refill. However, shortly thereafter, Robert came with his dromedary bag, and once the pump sealed well onto the receptacle, filling was a breeze… or at least I’m told. Robert did the bulk of the pumping, filling all three bags in under twenty minutes, a much better experience than I had with my Nalgene.

After our two hours were up, we were rested, fed, and resupplied, we donned our packs and began the ascent back to the truck. Our all-day exploration limited to two hours, it was a bit of a let-down to expectations, but in actuality, unless we planned to hike all day and bushwhack our way out of the main town, we had sufficient time to see everything that Beveridge had to offer. I can’t believe that there was a post-office servicing this town for a year… there isn’t much of a town to begin with! Our mission complete, it was time to wind our way back on an uphill again. You’d think after nearly 7,000 feet of climb, I’d be used to this, but I would say that ascent was the toughest of the trip, as I was already fairly tired, and was definitely looking forward to days of descent.

Returning along the path had one very large difference than arriving. Yes, we had more experience finding the cairns and had a pretty good idea of where the trails were heading, but there was an even easier way to find our path… our own footprints! By this time, we had a fairly good feeling of how we worked together as a team, and while there were some back and forths on who was doing what on the trip to Beveridge, for the most part on the return, we each had a particular role. I scouted ahead as far as the next bend, spending the time where I had additional speed to travel the trails, look around, and determine the correct path to take, while Vincent supported Robert as they persevered through the trails.

Also, having a chance to be ahead meant I had time to take some pictures of the area that I didn’t have time, or leftover concentration, for on the way into town. All-in-all, I took over 200 shots of the area during the trip, the majority of which were taken during the return.

While we mostly took about ninety minutes per mile traveling into Beveridge (by my GPS, that is), our return through the ascent and traverse was closer to an hour per mile. This boded well for our entire return journey. As we approached 6pm, we reached a large plateau that I believed was nearing the Great White Wall, though in actuality was about 2/3rds of the way through the traverse. This offered us a great place to find nice, level sleeping ground and wind down for the day. However, that feeling of relaxation was short lived, as it began to get very cold as the winds picked up… and I mean picked up. Looking at the weather data, we were experiencing 50 degree weather and 40 MPH gusts of wind through the night. Vincent built a wind shelter out of rocks, Robert sat and rested till he was ready to sleep where he sat, and I climbed into my sleeping bag early since I had the least clothing with me. It was a very eerie experience, hearing the gust build up in the valley before it actually reached us during the night. You could hear the howl very clearly, and knew to expect some strong gusts shortly thereafter.

Homeward Bound – Monday

While we encountered this at a few points along the hike in minor form, I think this is the place to address one piece of the preparation that was enlightening for me. Vincent has run a 50 mile trail run. I’ve completed a Half Ironman and most of an Ironman. I forget sometimes that one of the key things that athletes learn as they begin endurance training is how to eat while they train. Many people lose their appetite during exercise. Overcoming that is a learned behavior. One of my coaches once admonished us “Fuel Early, Fuel Often!” So on the large descent portion of the journey, when Robert was the most fatigued, Vincent had to regularly admonish him with “Eat, Dad! Eat!” Even though he is in the best shape of his life, that skill, fueling during exertion, is something that he likely has never had to encounter before. This proved to be a definite issue at times, as he would be severely lacking energy after a strenuous part of the hike, and Vince and I both knew what a part of the problem was. However, after you’ve bonked, it’s REALLY hard to have the stomach to get down food. Vince was regularly pushing more and more food on Robert, and watching him closely.. giving him two Honey Stingers on a break when he was likely willing to manage one, or hounding him until satisfied with the results. It was one of the few points of frustration on the trip, but serves as a good reminder of that piece of training that is so far behind me, I don’t even think about it any more.

While the last parts of the traverse continued to progress at the one mile, one hour pace as before, once we reached the ridge trail, and then onto the wall, our pace slowed down considerably, as this was the most difficult part for Robert to manage. Unstable footing is much easier to handle while ascending, but descending where you cannot trust your footing is quite difficult.

This especially held true when we got to the giant washout. There’s one section of trail where, instead of following a trail or switchbacks, instead you must scramble straight up (or down) a large washout. This means that there is no good way to know where you are or aren’t pickup up the trail, and there is zero solid footing to deal with. As the lead (or Billy Goat as Vincent put it later), I went part way down the washout, then unsure of where we’d catch up with the trail, headed off of the washout and climbed along the rocks beside it. I feel pretty confident scrambling around these steep areas, so I moved back and forth along sections of the washout, looking for where we’d pick up the trail.

In reality, I probably could have continued on the washout and found my way, but this was the role I was playing, and enjoying, so I was trying to do my best to minimize any delays for those behind me. The upside to this is that I got some fun rock climbing. The downside is that the pants I had spent way too much money on to handle this type of excursion didn’t survive the trek… at all. I got a giant cut all along my bottom as I was climbing over and around rocks.

The descent down the ridge, and down the wall, while long and difficult, were fairly uneventful compared to the trek in. All of us were surprised at how much rougher the trails were than we remembered them from just a day or two previously. We got to the bottom of the wall, stopped for about twenty minutes for a breather, and continued down the road. One last stop happened at our first night’s camp spot, where we relaxed for fifteen to twenty five minutes (depending on when each person got there), before making the final hour descent to the truck. That descent was fast, and it was a great relief to find ourselves back and the truck by 3pm, with time enough to make it home and sleep in our own beds for the night.

Last Impressions

KFWB GPS, the team that placed this epic geocache, GCB416, deserves grand kudos for bringing us out here. If the tone of this blog feels negative, it’s mostly because I like blogging about my learnings along these types of activities, and the process of blogging for me is quite self-reflective. I had a wonderful time going out and tackling this adventure with my family, and that never would have happened without Team Bardini’s drive to accomplish and tackle great things. It is an experience the likes of which I probably will never have again, and that in itself is a very rewarding feeling.